Since the 70s, emissions have been a major factor in the development of new automotive technology. It started with catalytic converters, then EVAP systems, and then OBD-II, which electronically monitors all emissions systems. Some emissions systems are just designed to curb harmful pollutants, while others are vital to the correct operation of newer engines.

Chances are, if there's a problem with one or more of your emissions systems, your check engine light (also called the malfunction indicator lamp, or "MIL" for short) is on. A lot of people have left their gas cap off and triggered the MIL, and wondered why it happened. It's more important than you think.

The switch from carburetion to fuel injection was not only for performance. Unburned fuel vapor from carburetors with the engine off creates more pollution than you might think. By closing the fuel system to the atmosphere, airborne hydrocarbons were reduced significantly, and the vapors in the tank were routed to the engine to be burned with the air intake. If you've ever owned a very old carbureted car and parked it in a garage, you know the smell of gas that it puts off just sitting there.

The car checks itself for leaks

EVAP systems of today are incredibly sophisticated, and can monitor leaks down to the thousandth of an inch. On a Volkswagen or Audi, it does so by monitoring vacuum loss in the fuel tank and EVAP lines. It sucks down the tank, closes off both ends of the system (vent valve on the tank and purge valve under the hood), holds it, and checks for vacuum loss. If there's a leak, it shows in the pressure differential. Now, if the gas cap is left off, air can get in the EVAP system, and the computer reads no change in pressure, which it determines to be a leak in the system. If the purge valve or vent valve do not close fully, it also interprets this as a leak. The EPA monitors EVAP emissions even with the car completely off, by putting it in a room and monitoring the room's air quality over time.

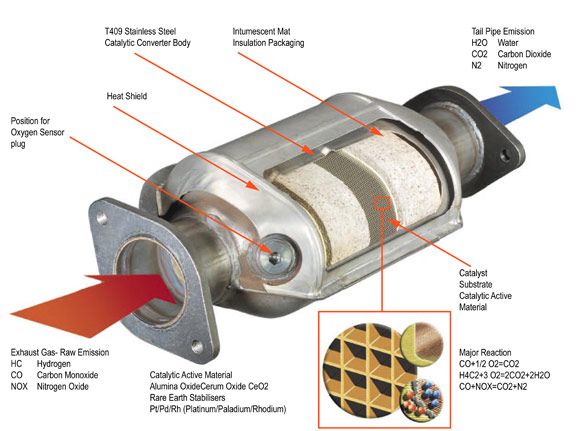

Catalytic converters

Catalytic converters are one of the oldest emissions systems. These serve no function other than emission reduction, and can actually rob your engine of power by increasing exhaust backpressure. Essentially, they are a honeycomb mesh of precious metals, usually platinum, and reburn the exhaust. As exhaust is passed through, it reacts with the platinum to heat the cats up to over 700 degrees celsius, and reburns the exhaust. While it doesn't fully clean the exhaust, it is currently one of the best solutions.

Secondary Air Injection

Secondary Air Injection

A newer emissions device is what's known as the secondary air system. It is an ingenious method of preheating the cats using an air pump. It pumps air into the cylinder head, behind the exhaust valves to dilute the exhaust from a cold start, effectively warming up the cats, reducing emissions even on a cold start. Once the cat is preheated, the secondary air system serves no real purpose.

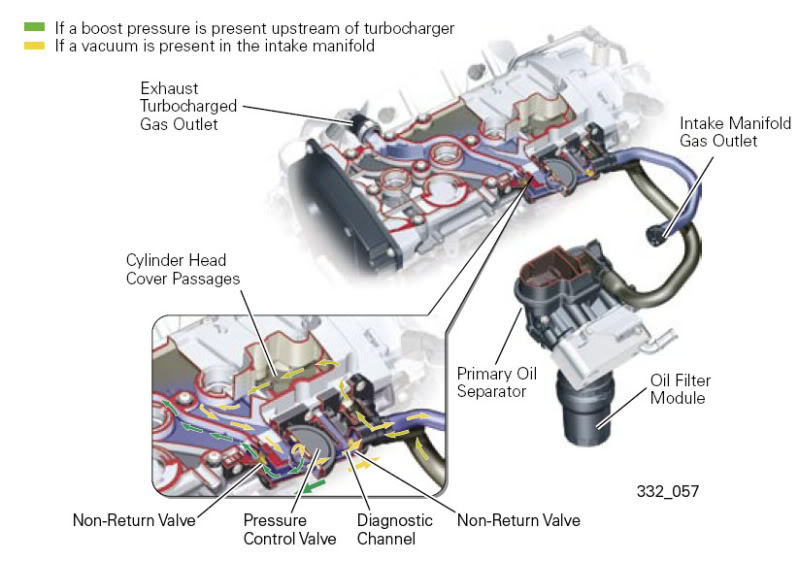

Positive Crankcase Ventilation

PCV systems are often referred to as emissions systems, but I don't think that's necessarily true. Certainly their function is to reduce emissions, but, unlike EVAP, catalytic converters, and secondary air, if there's an issue with the PCV system, you will have running and driveability issues. Since all intake air is so effectively metered, the air from a PCV in a late model Audi or VW is included in that, and a leak in the PCV can cause all kinds of running issues, like rough idle and weird fuel trims. Since their function directly relates to driveability, I don't think it's a bespoke emissions system.

Oxygen sensors play a crucial role in emissions regulations. Since air is monitored coming into the engine, it makes sense to analyse the exhaust coming out, via oxygen sensors. By determining the composition of the exhaust, you can tell if an engine is running lean or rich, and how to adjust the fuel injector duration, timing, etc. It can also determine if the cats are effectively working to reburn the exhaust. Again, I do not consider them an emissions device, since they play such an important role in an engine's driveability.

MIL on? Automatic fail.

The most important component of the emissions systems on a late model car is the MIL. Nine times out of ten, it serves to tell you that there is an issue with the emissions systems. If you have a misfire, it doesn't care that your car isn't running right, it cares that your catalytic converter isn't going to work properly because gas is pouring into it. If you have an issue with your EVAP system, it doesn't care that your car runs fine, it just cares that you could be releasing gas vapors to the atmosphere. If you don't believe me that the MIL is an emissions device, try and smog your car with a MIL on. It's an automatic fail in states that have mandatory OBD-II testing.

Now, in an OBD-II car (96 and newer), emissions systems are monitored. The cars run a system of self tests at various different times, unbeknownst to the driver, to determine the operation of all the aforementioned components. If they pass, it marks them as passed; if they fail, it sets a diagnostic trouble code (DTC), and potentially sets a MIL. In California, all the components must have passed their self-tests to be able to pass their biannual emissions test and be registered.

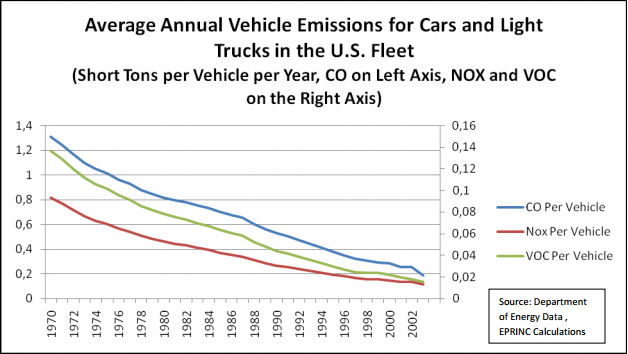

But are all these new systems in vain? Is it just some EPA scheme to sell catalytic converters? In short, no. Since 1970, emissions from cars and light trucks have dropped significantly. What this means is that we are getting closer and closer to the goal of a zero emissions engine, which will have little impact on the world around us. We may never get there, but the internal combustion engine is not dead yet.

About the Author: Chris Stovall

Chris is a journeyman mechanic from Berkeley, California, specializing in late model Volkswagens and Audis. A glutton for punishment, his spare time is spent rebuilding every component of his '83 Rabbit GTI.

Chris is a journeyman mechanic from Berkeley, California, specializing in late model Volkswagens and Audis. A glutton for punishment, his spare time is spent rebuilding every component of his '83 Rabbit GTI.