Pre-GM Saab vehicles are wonderfully unique cars in the automotive world. However, there are challenges in their ownership as we’ll show with this 1971 Saab 99 L.

Saab is one of those interesting companies that people just fervently hold on to, despite its later troubles after the GM bankruptcy. While the automotive division was started in 1949, Saab Aeroplan AB was founded in 1937 as a Swedish-based aircraft manufacturer. It was created to allow Sweden to produce its own aircraft during World War II since the US wasn’t willing to give up enough of its P-35s.

Ironically, this was a very similar reason as to why Saab created its automotive side. Most privately owned cars in Sweden were imported from the US – to which, US-made cars became limited since most US manufacturers were building war machines at the time – and waiting lists only grew after the war. Thanks to that, Saab formed its automotive division as a solution to that problem and first released the Saab 92. Less than two decades later, the Saab 99 was released in 1968 and its design would be the imprint for future cars from Trollhattan.

Despite its size and what we think of automobiles today, the 99 L was considered a “large family car” in Sweden. It was also a departure from Saab’s use of two-stroke engines as the 1.7-liter four-cylinder engine would be their first four-stroke engine.

This engine would see an increase in displacement to 1.85-liters in 1970 along with the introduction of the 99 L.

Getting stale air out of the cabin was done through a vent in the quarter panel that could be opened and closed from the inside. This vent would become another staple of Saab design as we would see on the “classic” 900. Another interesting rear feature of the 99 was its rear window defroster that used heated air rather than an electrical heater element embedded into the glass.

What probably surprises many people in the US is the use of Hella products on the Saab 99. We usually associate them with aftermarket and racing lighting – especially in the FIA World Rally competition – rather than making parts for auto manufacturers. The reality is that Hella has been an OEM provider for decades and many of us just didn’t notice it.

The name “Hella” is a play on the German word “hell” which roughly translates to “bright” in English, but the name is also credited to the wife of Hella founder, Sally Windmuller. Originally, Hella was founded in 1899 as WMI to produce ball horns, candles, and eventually kerosene lamps for horse-drawn carriages. They even held a patent on acetylene headlights as early as 1908.

Saab was full of introductions at the time. In 1970, the Saab 99 also introduced the world to the idea of the headlight wiper and washer. What makes this version even more unique is that it is a linear wiper.

The blade moves straight across the headlight rather than in an arc as we see in later versions from other manufacturers. This not only cleans the headlight of snow but also washes dirt from the glass with its washer nozzle that is mounted just inside the housing. Therefore, Saab would promote it as a safety feature and headlight wipers would become mandatory in Sweden after their introduction on the 99.

This is another clue that this 99 wasn’t originally a US-destined car. The Saab 99 that would have come to the US would feature two round, sealed beam headlights as required by the US National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Instead, the European-sold Saab 99 used a single Hella H4 bulb inside its Hella glass headlight housing.

This 99 is a Swedish built and sold car that was imported by its first owner, Dr. Forst. It remained in the good doctor’s ownership until the current owner, Dallin Jo Jolley, purchased it about two-and-a-half years ago.

If you’re unfamiliar with Halogen lighting history, European cars used Halogen lights since 1962 with the introduction of the H1 bulb design. The H1 is a single element bulb, so it could only be used in a single beam application and meant that you’d need an H1 bulb for each beam pattern. By 1971, however, the dual filament H4 bulb was introduced and you could then have a high and low-beam headlight from a single source.

These two features don’t just make this Saab 99 look better than a US-sold one, but also provides far better lighting than the sealed-beam version.

The new owner, Dallin Jo Jolley, has always been a fan of Saabs, “my elder brother’s first car was a 1987 Saab 900 Turbo.” Dallin is also the president of an architecture startup, Modal Living, that specializes in designing shipping container-sized dwellings. His love for design explains his affection towards the 99. “I fell in love with the quirky features and the long, sloped back-end,” he said. “The engineering was different and purposeful in the 99 L.”

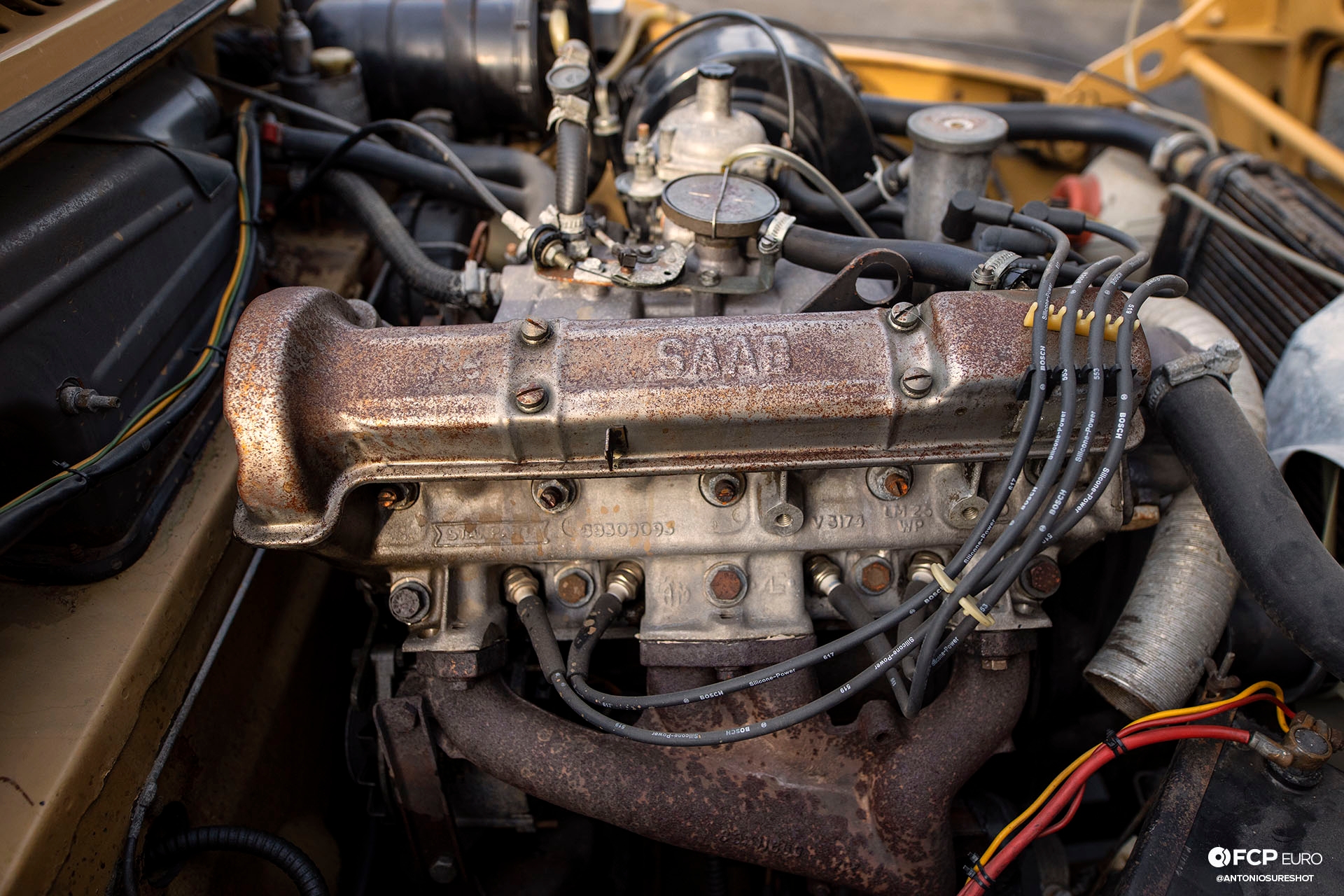

While that may say “Saab” on the cam cover, this is a Triumph slant-four. Up until the introduction of the 99, Saab had only built inline two-cylinder and V4 two-stroke engines. They had no experience in building a four-stroke but were in the process of developing one. That is, until they realized it would be too risky and expensive to tackle on their own. That’s when they decided to source and use the slant-four from Triumph from 1968 until the introduction of the Saab B-engine in 1972.

The unusual design of the slant-four comes from its 45-degree cylinder inclination from crankshaft vertical. The idea was to make it modular with their 90-degree V8 engine tooling since each bank would be 45-degrees from crank centerline. This choice made production cheaper for Triumph and, subsequently, Saab.

The aluminum, overhead camshaft head also used wedge-shaped combustion chambers and put the spark plugs between the two valves where the casting is thicker. The “Siamese” exhaust port on the center two cylinders is more down to the casting of the exhaust manifold. A cast manifold with three runner branches is far easier and less costly to cast over one with four individual runners. It is a similar reason the original small-block Chevrolet V8 used a comparable cast manifold and exhaust port design, despite being a pushrod engine.

The slant-four was also a carburetor engine from both Triumph and Saab, but Saab used a single Zenith-Stromberg 175 CD-S that was made just for their use of the slant-four.

Which explains this interesting box attached to the air cleaner. With the lever flipped to “Summer,” this allows ambient temperature air from the engine bay to reach the air cleaner. Flip it to “Winter” and this leads to a tube that normally attaches to the exhaust manifold and allows hotter air to reach it.

Colder air is denser than warmer air, which means you have more air molecules packed in that colder air than warmer. If your carburetor is tuned to run in warmer air, the fuel jetting will be wrong for the oxygen dense cold air, and the engine will run too lean. That means you’ll have more air than fuel for your combustion mixture which isn’t good. The opposite can happen in warm air, where the less oxygen dense air will make the engine run too rich since the carburetor is allowing more fuel in.

The solution for OEMs at the time was to attach a tube to the exhaust manifold to draw up the warmer air for the carburetor and allow the engine to run with the correct air-fuel ratio. Well, close to the correct air-fuel ratio, anyhow. We don’t have this now because the ECU makes the changes to the amount of fuel being injected by reading the various sensors in and around the engine.

You’ll probably notice another interesting feature of the Saab 99 via this radiator shot. Not so much in the use of an electric fan, but how the engine is placed in the engine bay.

This becomes more evident when you realize the alternator isn’t at the “front” of the engine and see that it is located at the “back.” The way Saab employed its front-wheel drivetrain was by using a triplex chain-drive at the clutch output that leads down to the input shaft of a transaxle and allowing it to rotate in the correct direction for forward movement.

That transaxle was mounted to the bottom of the engine and, essentially, the transaxle was also the oil pan. Despite this, the engine oil and transaxle oil were separate from each other and each had their own drain plug. This transaxle design was another Saab feature that lasted through to the end of production of the “early” 900 in 1994.

A consideration that needs to be taken, thanks to its spark plug location, is the use of high-quality silicone spark plug wires. With the plugs being so close to the exhaust manifold, it is critical that the boots can withstand much higher temperatures than plugs mounted overhead or near the intake manifold. This makes Bosch Silicone-Power wire sets a smart choice since their boots can withstand a large range of under-hood temperatures.

Most older cars also respond better to standard, copper-style plugs like the Bosch Super Plus spark plug. This type of spark plug is usually cheaper but will match the mileage for replacing the wires as part of your regular maintenance.

Maintenance is a key issue to tackle correctly when owning an older car, as well. Many parts will have been on these vehicles for many decades and will eventually fail due to age and wear. Overheating issues, for example, can arise from rubber parts rotting away and building up in the water passages in the engine. Belts loosen over time, metal corrodes or oxidizes, and many other issues will appear if you don’t maintain a vehicle. This is true regardless of a vehicle’s age, but it is far more important to an older car with its older technologies and materials.

An older vehicle that just sits instead of drives can also have issues ranging from temporary (like tires that develop flat spots from sitting too long) to more complex (like batteries building up scale inside them without regular charging and discharging or fuel that has gone “stale”). That’s what occurred during our shoot of Dallin’s 99 L. It developed an overheating issue that Dallin was able to resolve, but that is part of the challenge of classic car ownership.

The idea of aircraft design was never lost on Saab and that methodology is how it approached vehicle design. Parts like their large, wrap-around windshields gave drivers a better view in front of them. Saab engineers made sure that controls were easily in reach, too. This type of engineering is the reason many designers and engineers desire a Saab. The brand creates well-thought-out vehicles from start to finish and their fans appreciate that.

Of course, being an import from a metric-measuring country can have its challenges. The speedometer, for example, is in KPH and the 50 mark you see here is about 31-MPH. If you’re doing that on the highway, you’re probably getting death stares, even as you are driving in the right-hand lane.

That aircraft mentality is seen in the interior design, too. A philosophy that dictates that the driver isn’t distracted from the task of driving. The steering wheel, for example, is a very simple, two-spoke design that never gets in the way of the instrumentation during normal driving. There are no gizmos or games to take the driver’s attention away from driving.

Interestingly, the ignition switch is located on the center console instead of the dashboard. You’ll also see that the cabin rear vents (that are connected to the vent openings on the rear quarter panels) and rear window defroster controls are located here.

The air for the rear window defrosting comes from the same heating system for the passenger compartment. This lever closes off the vent tubes that run under the center console to shut off the rear window defroster. The toggle switch just above the ignition switch is for turning the interior lights on and off.

Since this was built in 1971, the seats didn’t come with headrests as standard equipment. These “art deco” inspired headrests were an option when this car was new and are unique to the 99.

The transmission on this 99 L is the Saab G34 four-speed transaxle, the same one used on the early 900 before that was switched to a five-speed transaxle.

Originally, the 99 didn’t come with a radio at all, so this is an aftermarket installation including its housing and single paper speaker. While this has a “GM” logo on it, it appears to be an aftermarket, dealer-installation radio made by Philips for GM. It is most likely an early version of the Philips Sprint, a mono-output AM/FM radio that saw use GM-owned European brands.

The lack of a radio also means that the door cards don’t have any provisions for speakers. That aftermarket mono radio installation was the only way for the original owner to get any type of entertainment outside the enjoyment of driving.

If you’ve never driven a vehicle that had a carburetor and manual choke, you probably have no idea what any of that means or what a choke lever does. The choke valve reduces the amount of air going through the carburetor to richen the air to fuel mixture.

Even though we mentioned the Winter/Summer switch earlier, this is a different case. On a “cold” engine – an engine that’s not to operating temperature – the atomized fuel doesn’t completely reach the combustion chamber. Colder air typically pools up rather than staying atomized in the intake manifold and this results in less fuel reaching the combustion chamber.

The carburetor needs to add more fuel to the air to fuel ratio – in other words, run richer – to make up for that until the engine has reached its minimum operating temperature. Usually, once it starts and runs for a few seconds and the intake air temperature rises, you can reset the choke and allow more air in.

Unlike most cars, the handbrake in the Saab 99 operates on the front wheels rather than the rear.

Despite the interior’s generous size and the trunk space of the 99, the previous owner decided to install this roof rack for even more luggage carrying options.

“I really just enjoy driving it,” says Dallin, “It is so well balanced with enough power to feel peppy but not too much to get out of hand. It is incredibly smooth with its power delivery and handling.” Of course, a Saab is going to gather attention, “I take it to local car meets and, as simple as it is, it gets so many head turns. It is an automatic conversation starter that everyone falls in love with.”

The only disappointing part for Dallin is that he doesn’t get to drive it enough. Modal Living is headquartered in Salt Lake City, and he travels between Utah and Marina Del Rey, California where the 99 L is garaged. This can make classic car ownership a challenge since he’s normally far away from it and not able to drive it how he needs and wants to. However, that garage life has been mostly positive since it hasn’t been molested by the environment or twitchy hands.

This 1971 Saab 99 L is a time capsule that only just does show its age. It is a beautiful reminder of what Saab was and why those engineers and designers long for this brand and its return. Hopefully, one day, we’ll see Saab rise from the ashes and return to its glory. Otherwise, this 99 L and Dallin Jo Jolley will help us remember the best times of Saab.

Story by Justin Banner

Photos by Antonio Alvendia